Youth Mental Health

There is a growing mental health crisis among America’s youth. Data show that anxiety is commonly diagnosed in youth (8.5%), followed by behavior disorder (6.8%), and depression (3.8%). Approximately 1 in 6 youth reported making a suicide plan in the past year, a 44% increase since 2009.

Youth with poor mental health are more at risk of social exclusion, discrimination, stigma, difficulty learning, and poor physical health. The gravest health threats to teenagers used to be binge drinking, drunken driving, teenage pregnancy, and smoking, but recent data reveal a new concern: sharp increases in mental health disorders. Data from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicated that the percentage of youth between 12-17 years who reported experiencing a past-year major depressive episode (MDE) has doubled over the past decade.

Physical, emotional, and social conditions like exposure to poverty, abuse, or violence can increase adolescents’ vulnerability to mental health problems during a critical time, as they develop social and emotional habits that impact mental well-being, like healthy sleep habits, regular exercise, problem-solving and interpersonal skills, and managing emotions. Risk factors that increase youth stress include exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), social media influence and pressure to conform with peers and identity norms, severe socio economic problems, and health insurance status.

A landmark study of over 10,000 youth found that climate change, natural disasters, and lack of governmental action have had a devastating impact on the mental health of youth, including increased trauma, anxiety, depression, feelings of abandonment and suicidal ideation. More than 45% of respondents said their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning.

School connectedness, opportunities for adult mentorship, and sense of belonging are important protective factors to poor mental health. School counselors, nurses, social workers, and psychologists are often the first to identify children who are sick, stressed, traumatized, acting out, or at risk of hurting themselves or others. While schools are ripe for integrating mental health treatment and prevention services, most states lack comprehensive policies and social-emotional learning opportunities. A widely-adopted strategy is school personnel intervention and provision of more funding for school counselors and social workers through expanding Medicaid to cover services outside of the Individualized Education Plan (IEP). In some cases, community based mental health providers deliver services in schools.

There are countless grassroots and community efforts to improve mental health including the Parent Support Network, which educates families and caregivers on how to support youth, AIM, which funds and implements evidence-based treatments while training adults in mental health first aid, Mental Health America, which advocated for helped to pass the first law in the nation requiring schools to teach students about mental health. Considering how mental health has continued to decline during COVID-19, more urgency is needed at all levels of government and institutions to enact policy changes and programs that promote mental well-being.

Youth who are of color, disabled, LGBTQ+, low-income, living in rural areas, in immigrant households, in the child welfare or juvenile justice systems, and/or unhoused are particularly vulnerable to poor mental health. Approximately 25.5% of American Indian or Alaskan Native youth, 11.8% of Black youth, and 8.9% of Hispanic youth reported attempting suicide in the past year, compared to only 7.9% of white youth.

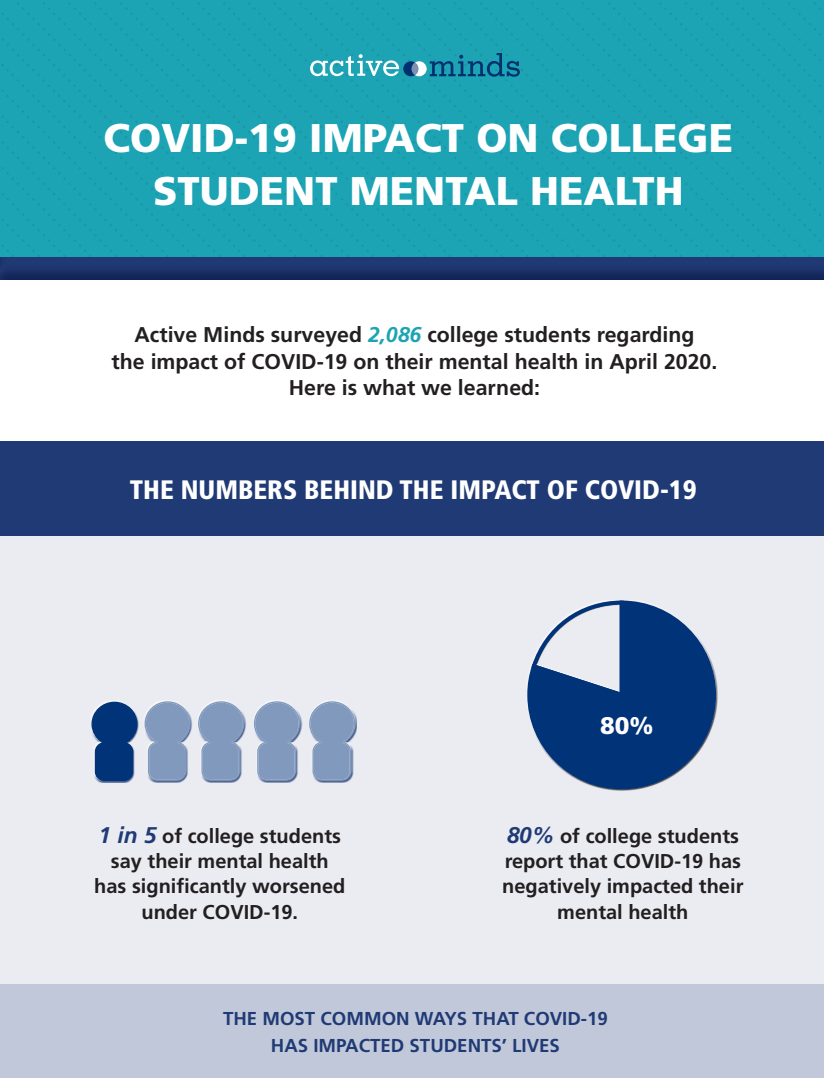

This crisis was exacerbated by COVID-19, which increased isolation, potential for emotional abuse by parents or caregivers, and socioeconomic difficulty. In 2021, more than a third of high school students reported that they experienced poor mental health during the pandemic, and 44% of students reported that they persistently felt sad or hopeless during the past year. Poor mental health increases risk of drug use, experiencing violence, high-risk sexual behavior, and difficulties with learning and decision-making.

Telemental health and school-based services are particularly effective in addressing inequities for students of color and should be funded accordingly. Every child should have access to high-quality, affordable, culturally competent mental health care, and efforts should be evaluated rigorously to address gaps in student access. Policies must address economic and social barriers that contribute to poor mental health for young people.

Millions of youth are in schools with police, but without counselors, nurses, psychologists, or social workers. This lack of school-based behavioral resources can lead to help requested from law enforcement, which can lead to overcriminalization and alienation of students, particularly those with disabilities and students of color. Legislation should support positive discipline practices like restorative justice, social-emotional learning programming, increased funding for mental health services, improved data collection, and prevention of guns on school property.

Youth leaders are powerful advocates for achieving policy changes and connecting peers with resources; additional investment in the training and education of youth leaders can help drive improvements in youth mental health. Many state-level Departments of Education are using COVID-19 recovery dollars to hire school counselors, social workers, and nurses, to implement meaningful summer learning and enrichment opportunities, to partner with community based organizations and Certified Community Based Behavioral Health Centers (CCBHCs), and to train youth peer leaders.

Resources & Tools

Taking Action to End Gun Violence: Our Top Tools, Resources, Stories, and Data

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

Beyond Inclusion: Pronoun Use for Health and Well-Being

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

Colorado SB 20-001: Expand Behavioral Health Training for K-12 Educators

Resource - Report

Brought to you by Health Impact Project

The Time to Act Is Now: Investing in LGBTQIA2S+ Student Mental Health in K-12 Schools With a Youth-Centered Approach

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by Society for Public Health Education

The Intersection of Housing and Mental Well-Being: Examining the Needs of Formerly Homeless Young Adults Transitioning to Stable Housing

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by NLM

A Review of the Domains of Well-Being for Young People

Resource - Report

Brought to you by Urban Institute

Adverse Childhood Experiences: The Protective and Therapeutic Potential of Nature

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by Frontiers

Cops and No Counselors: How the Lack of School Mental Health Staff Is Harming Students

Resource - Report

Brought to you by ACLU

Association of Recent Violence Encounters With Suicidal Ideation Among Adolescents With Depression

Resource

Brought to you by JAMA

Association of Firearm Access, Use, and Victimization During Adolescence With Firearm Perpetration During Adulthood in a 16-Year Longitudinal Study of Youth Involved in the Juvenile Justice System

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by JAMA

Neurodiversity and Gender-Diverse Youth: An Affirming Approach to Care 2020

Resource - Guide/handbook

Gender Variance Among Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Retrospective Chart Review

Resource - Journal Article

Implications of Internalised Ableism for the Health and Wellbeing of Disabled Young People

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Contagious Conversations: A CDC Foundation Podcast

Resource - Podcast

Brought to you by CDC Foundation

Mental Health and Substance Use Considerations Among Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Resource - Policy Brief

Brought to you by KFF

Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence

Resource - Report

Brought to you by CDC

Falling Through the Cracks: Graduation and Dropout Rates Among Michigan’s Homeless High School Students

Resource - Policy Brief

Brought to you by University of Michigan

Colorado SB 20-014: Excused Absences in Public Schools for Behavioral Health

Resource - Report

Brought to you by Health Impact Project

Roadmap for Resilience: The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health

Resource - Report

Brought to you by Office of the Surgeon General of the United States

The Relationship Between Mental Health Care Access and Suicide

Resource

Brought to you by RAND Corporation

50,000 Children: The Geography of America's Dysfunctional and Racially Disparate Youth Incarceration Complex

Resource - Fact Sheet

Brought to you by Youth First

Autism Spectrum Disorders in Gender Dysphoric Children and Adolescents

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by Springer

COVID-19 and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: The Pandemic's Influence on an Adolescent Epidemic

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by APHA

Adverse Childhood Experiences: Health Care Utilization And Expenditures In Adulthood

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by Health Affairs

The Role Youth and Young Adults Play in Mental Health Legislation

Resource - Blog

Brought to you by Active Minds

The Mitigating Toxic Stress Study Design: Approaches to Developmental Evaluation of Pediatric Health Care Innovations Addressing Social Determinants of Health and Toxic Stress

Resource - Journal Article

Brought to you by NLM

Seven Things You Should Know About Childhood Poverty

Story - Written

Brought to you by Community Commons

Gun Violence Becomes Leading Cause of Death Among Us Youth, Data Shows

Story - Written

Brought to you by The Guardian

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Young Men of Color

Story - Written

Brought to you by Community Commons

Mental Health Crisis Centers and EmPATH Units: Offering Care That Busy ERs Can’t

Story - Written

Brought to you by STAT

Published on 04/26/2024

Race-Based Stress and Intergenerational Trauma

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

Published on 09/16/2022

Racism Has Youths of Color Seriously Stressed Out

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

Published on 03/09/2017

Intro to Traumatic Stress: Trauma, Stress, and Trauma-Informed Practice for Community Health and Well-Being

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

The Student Stress Crisis: What is Portland State Doing to Make a Difference?

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

Telemental Health Provides Opportunity to Improve Population Mental Health

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

When the Biggest Student Mental Health Advocates Are the Students

Story - Written

Brought to you by NYT

Published on 02/06/2024

Adverse Childhood Experiences – Trauma in Children Across the Nation

Story

-

Original

Original

Brought to you by Community Commons

Published on 12/19/2017

Data & Metrics

Related Topics

.jpg)