Racism Has Youths of Color Seriously Stressed Out

- Copyright

- 2017

- Published Date

- 03/09/2017

- Published By

- Community Commons

This article was written by Shari Sharpe, editorial intern. It was originally published on TakePart in November 2016.

Thanks to the ongoing effects of systemic racism, research shows black people living in the United States aren’t as healthy as their peers in Canada. Now a new study reveals some of the race-related stressors—such as police violence and gentrification—that are impediments to health and wellness for young people of color in America.

“Many young people of color in the study cite feeling over-policed, undervalued, and unsafe in their own communities as barriers to wellness,” Jonathan Zaff, executive director of the Center for Promise, said in a statement. “These feelings often stem from pervasive stress and trauma associated with a lack of access to high-quality nutritious foods and medical care and concerns of racial discrimination that can lead to risky behaviors and a distrust of institutions. The result is entire generations growing up in constant fear, which affects their lives and can limit their potential in so many ways.”

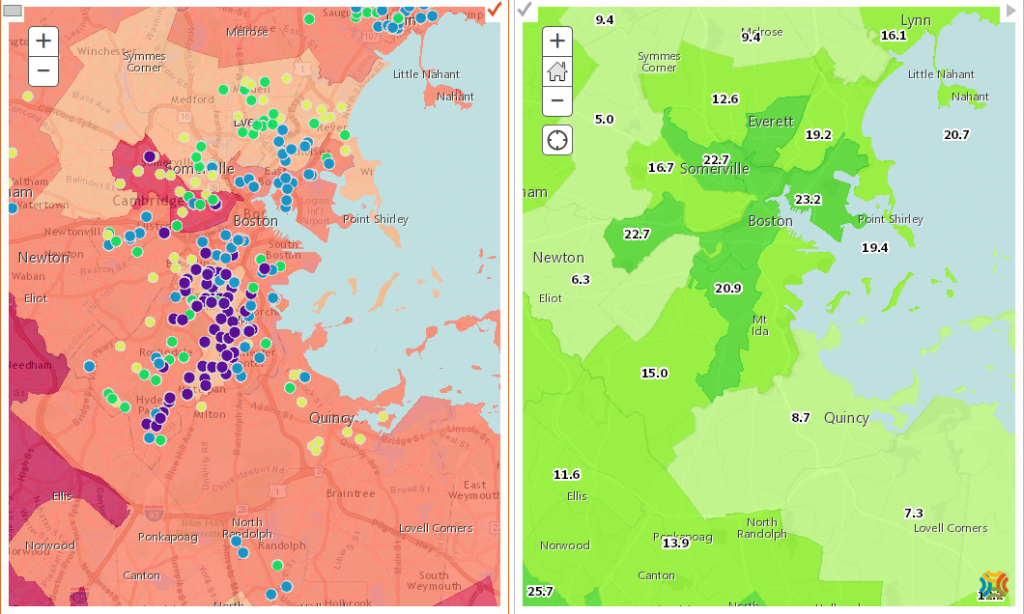

Left: Population, African American, Age 5-17 (2008-2012) Right: Population, African American, Age 5-17 (2011-2015)

Addressing the well-being of children and youths of color is critical: They’re the fastest-growing demographic in the United States and the majority of the youth population in roughly half of the 100 largest cities in the nation. To gain a better understanding of the barriers this demographic faces, the center decided the health and wellness assessment should be designed and implemented by young people. Youths ages 13 and up created questionnaires and interviewed their peers. The study is, according to the center, the first multicity, youth-led community health assessment to be conducted in the U.S.

Sixty percent of respondents from Chicago said they believe that youths are antagonized by police. To avoid police interactions or surveillance, the Chicago respondents said they are more likely to stay indoors—at friends’ houses or at their own homes—than go out in public. “Kids can’t freely walk or play in the community without being worried about getting beat up or shot and killed,” one person told a youth researcher. This, in turn, makes youths of color less willing to leave their communities—which are frequently food deserts—to find healthier food options.

The Philadelphia team of youth researchers used a “photovoice” method to study stereotyping—which the study defines as “a form of visual ethnography employed by community action and health promotion researchers to catalyze community change.”

They found that young people naturally begin to feel unwelcome or unsafe given the amount of stereotyping and racism they are subject to or witness. Negative stereotypes of clothing, hair, gender, or race become internalized, leading to impacts on the mental well-being and self-esteem of youths of color.

“It boils down to the environment, in my opinion. If we don’t see more positivity around us, we’re likely to behave negatively and, in an already impoverished state of mind, we act based off of survival,” said a St. Paul survey respondent. “We’re afraid to talk about our problems because we either feel like no one’s listening, cares, or we don’t want to seem inferior,” said the survey respondent.

Given that racial bias begins in preschool and that it’s tougher for people of color to find a therapist, improving the health of youths of color won’t be easy. “Youth-serving organizations, educators, and local political officials should be equipped with the appropriate training to create safe spaces for racial healing, particularly for youth of color who have experienced traumatic events with community violence and police brutality,” recommends the center.

Otherwise, young people will keep “growing up in constant fear, which affects their lives and can limit their potential in so many ways,” Zaff said.

View StoryRelated Topics